Cybersecurity Fundamentals

Final Project Blog Post

Final Project Blog Post

Today, let’s talk about the biggest cyber incident you’ve never heard of: the MOVEit breach. The MOVEit security breach affected over 2500 organizations and 95 million individuals [1]. The reason for both the huge scope as well as the relative unknown-ness of the breach is because this was a supply chain attack. ORX, a risk management association for financial services, describes the breach as a “hydra-headed breach” that “rippled up and down the complex digital supply chain” impacting many vendors and organizations [2, p.2]. MOVEit is a file transfer program made by a company called Progress Software Corporation [1]. It is basically a platform that facilitates the secure transfer of files, rather than an organization having to build out their own solution. This particular platform is very popular, used by thousands including governments, financial institutions, and others. Progress Software describes themselves as a AI and infrastructure software company with products to help you reach your business goals [3]. Basically, Progress Software’s MOVEit is a pre-packaged solution to a problem that many organizations have: secure file transfer. Progress has built up a reputation and people put their trust in that reputation to keep their files secure as they are moved between datacenters or for “big data” analysis. This actually became part of the problem. With so many high value targets putting their eggs into file transfer programs’ baskets, file transfer tools in general, not just MOVEit, became a prime target. The Washington Post commented that file transfer tool hacks were common in 2023 [4].

What Happened?

So what happened? In 2021 a Russian speaking hacker group known as TA505 developed a ransomware codenamed Cl0p. This ransomware became so prolific and well known that it became a pseudonym for the group itself [2,5]. The first evidence of Cl0p using the zero-day attack, or an attack which the software creator is unaware of, is all the way back in 2021. Zero-day exploits are highly sought after because they provide attackers with a window of opportunity before defenders can react, and then they still get time because they have to determine and build the fix. Logs indicate what appears to be manual exploitation of the vulnerability, suggesting that Cl0p was carefully figuring out how to use it. Throughout 2022 Cl0p worked on perfecting their access, beginning to use automated attacks, as indicated by the timestamps and rapidity of accessing and enumerating underlying systems [2]. It was then in 2023, deliberately timed before a holiday when there would likely be less staff watching for anomalies, that Cl0p finally executed the attack. This is actually a common tactic in major ransomware campaigns.

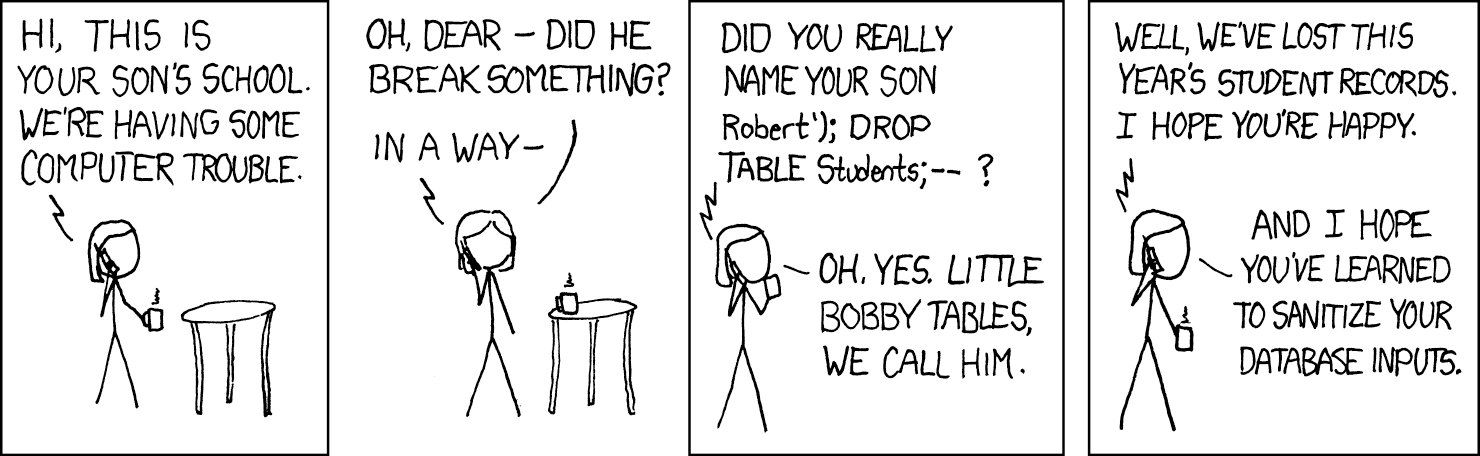

Figure 1: “Exploits of a Mom,” by Randall Munroe, xkcd.com.

The Attack Chain

The attack itself started with a SQL injection attack. The Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) shows us that a SQL injection attack is when an attacker enters, or “injects” a SQL command into a data field with the intent of interacting with the underlying SQL database. A successful SQL injection exploit can allow an attacker to read data from the database, modify the database, either by writing, changing, or even deleting data, or in some cases execute commands or programs [6]. In the case of MOVEit, Cl0p used the SQL injection to install a customized webshell called LEMURLOOT. A webshell is malicious script that is uploaded to an existing web server. It listens for carefully crafted HTTP requests and responds, giving attackers a persistent backdoor with the web server's permissions. Before we travel too far down the attack chain, lets address the elephant in the room. The thing about SQL injections is they are generally easy to protect against. The counter to a SQL injection is input validation. SQL injection relies on using special characters that have meaning to a SQL server and can then be interpreted as commands. For example a single quote could be used to prematurely end the text field that the application is asking you to fill, and then a semicolon end the command, allowing the attacker to input a new, second command. Input validation simply examines the content of the field before passing it to the SQL server and either sanitizes it by commenting out the special characters so the server does not interpret them as commands, or by rejecting the input and asking the user to try again. According to Holden, as cited by Plumb in SDXCentral [7], the entire event was caused by “very sophomoric-level vulnerabilities found within the MOVEit software.” Once the LEMURLOOT web shell was deployed (disguised as human2.aspx to look like the legitimate file human.aspx) it acted as a persistent backdoor and allowing the attackers to send commands via HTTP headers. These commands included querying the MOVEit database, creating temporary admin accounts, and downloading files. They even collected Progress Software customer’s Azure storage keys and were then able to pivot to downloading files from Azure [2,5,7]. Once Cl0p had the files, they began sending ransom demands, and if the customers didn’t pay, they published the files on leak sites, or, as a first for Cl0p, as torrents. Torrents made the data much more resilient against take-down requests as torrents are decentralized [2].

In summary, Cl0p used a zero-day vulnerability that affected even the most well-managed systems, since there was no patch for it. They moved fast, but even after the patch was released, customers had poor patch management and remained vulnerable. A lot of the mass exploitation happened here. Many customers had poor logging, or just didn’t check their logs and didn’t even know they were compromised until Cl0p announced it. Without logs, you’re blink, both during and after an attack. A final factor in the attack we’ve already touched on, is because of what MOVEit is: a secure file transfer tool. As such it had direct access to the most sensitive files that need to be transferred securely.

Affected Organizations & Scale and Aftermath

The MOVEit breach affected over 2,500 organizations and 95 million individuals. Organizations included British Airways, BBC, the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, the University of Rochester, the Oregon Department of Transportation, the Louisiana Office of Motor Vehicles, and so many more. One of the top affected organizations, Maximus, is a service delivery vendor targeting Government agencies. They had over 11 million individuals records leaked.

Typically the term “widespread threat” is reserved for events or attacks that have many attackers and many targets. However, according to Ars Technica [8], security firm Rapid7 made an exception even though there was only one known attacker: Cl0p. This was because this wasn’t script kiddies, or low skill attackers just throwing out exploits, this was the deliberate and skillful exploitation of high-value targets across the globe. I have to agree, this was a widespread threat. Emsisoft [1] reports the estimated cost per record leaked at an average of $165. All together that puts a conservative estimate of the cost, not including any leaked intellectual property at over $15 billion. For this reason the MOVEit breach is called one of the most expensive cyber incidents, ever. And none of that includes lost revenue due to reputational damage, regulatory fines, or the many lawsuits that came after!

Prevention and Mitigation Stragegies

We already mentioned how the vulnerability was a zero-day, and no patch was available, however, good secure coding practices would have prevented such a juvenile SQL injection attack. MySQL, a common implementation of SQL, even has a function to automatically sanitize input called real_escape_string(). Of course other common aspects of defense-in-depth apply as well, such as continuous vulnerability scanning, and rapid patch deployment. Also common items like effective logging and auditing, and systems for tracking exceptions, such as large amounts of data being exfiltrated. Because this exploit used the permissions of the web service account, the principle of least privilege could also be applied. This would help segment access if an attacker did get access, preventing them from moving laterally within the system. Putting a web application firewall (WAF) in front of the application would also help. A WAF, also called an application layer firewall doesn’t work on just ports and protocols, but examines the actual traffic. It could see and block common SQL injection patterns.

Conclusion and Lessons Learned

In my opinion, the biggest lesson to learn in all of this is supply-chain risk management. Along the lines of the very buzz-word zero trust, we can’t just trust that everyone we use is doing the right thing. Thousands of organizations trusted that Progress Software created a secure application. Because of that trust, they gave that application direct access to their most sensitive files. Some organizations didn’t even know they had been breached simply because they didn’t use MOVEit, but a contractor of an affiliate that had access to their data utilized MOVEit. This isn’t just about MOVEit by Progress Software. It is about the entire software supply chain. As I mentioned, secure file transfer software was a common target in 2023 and even before. First Accellion, the GoAnywhere, and finally MOVEit, among others. While it is undeniably critical that vendors secure their code, organizations have to stay on top of their vendors, requiring security attestations and auditing. Again, the lack of logging didn’t help at all. Some victims didn’t even know they were victims until Cl0p posted their name. Visibility into your own systems matters just as much as prevention.

[1] Z. Simas, “Unpacking the MOVEIT breach: Statistics and analysis,” Emsisoft, https://www.emsisoft.com/en/blog/44123/unpacking-the-moveit-breach-statistics-and-analysis/ (accessed Jul. 25, 2025).

[2] I. Selwyn, “MOVEit Transfer Data Breaches,” ORX News, Geneva, Switzerland, report, Nov. 9, 2023. [Access requires ORX News registration].

[3] Progress Software. https://www.progress.com/company

[4] T. Starks, “Cyberdefenders respond to hack of file-transfer tool,” The Washington Post, Jun. 7, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/06/07/cyberdefenders-respond-hack-file-transfer-tool/ [Archived at: https://archive.is/20230607140247/https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/06/07/cyberdefenders-respond-hack-file-transfer-tool/]

[5] Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, “#StopRansomware: CL0P Ransomware Gang Exploits CVE-2023-34362 MOVEit Vulnerability,” Jun. 07, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/cybersecurity-advisories/aa23-158a

[6] kingthorin and zbraiterman, “SQL Injection,” OWASP Foundation. [Online]. Available: https://owasp.org/www-community/attacks/SQL_Injection. (Accessed: Jul. 30, 2025).

[7] T. Plumb, “Dissecting the MOVEit breach: Lessons learned from the ransomware attack,” SdxCentral, Sept. 11, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sdxcentral.com/analysis/dissecting-the-moveit-breach-lessons-learned-from-the-ransomware-attack/

[8] D. Goodin, “Mass exploitation of critical MOVEit flaw is ransacking orgs big and small,” Ars Technica, Jun. 5, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2023/06/mass-exploitation-of-critical-moveit-flaw-is-ransacking-orgs-big-and-small/